Spectral radius

In mathematics, the spectral radius of a square matrix or a bounded linear operator is the supremum among the absolute values of the elements in its spectrum, which is sometimes denoted by ρ(·).

Contents |

Matrices

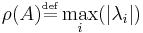

Let λ1, ..., λn be the (real or complex) eigenvalues of a matrix A ∈ Cn × n. Then its spectral radius ρ(A) is defined as:

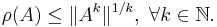

The following lemma shows a simple yet useful upper bound for the spectral radius of a matrix:

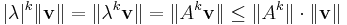

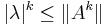

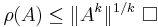

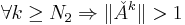

Lemma: Let A ∈ Cn × n be a complex-valued matrix, ρ(A) its spectral radius and ||·|| a consistent matrix norm; then, for each k ∈ N:

'Proof: Let (v, λ) be an eigenvector-eigenvalue pair for a matrix A. By the sub-multiplicative property of the matrix norm, we get:

and since v ≠ 0 for each λ we have

and therefore

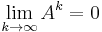

The spectral radius is closely related to the behaviour of the convergence of the power sequence of a matrix; namely, the following theorem holds:

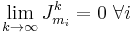

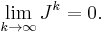

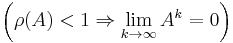

Theorem: Let A ∈ Cn × n be a complex-valued matrix and ρ(A) its spectral radius; then

if and only if

if and only if

Moreover, if ρ(A)>1,  is not bounded for increasing k values.

is not bounded for increasing k values.

Proof:

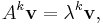

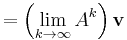

Let (v, λ) be an eigenvector-eigenvalue pair for matrix A. Since

we have:

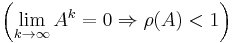

and, since by hypothesis v ≠ 0, we must have

which implies |λ| < 1. Since this must be true for any eigenvalue λ, we can conclude ρ(A) < 1.

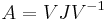

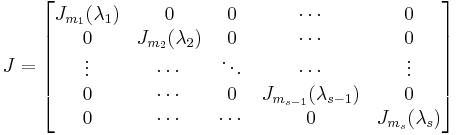

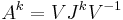

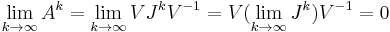

From the Jordan normal form theorem, we know that for any complex valued matrix  , a non-singular matrix

, a non-singular matrix  and a block-diagonal matrix

and a block-diagonal matrix  exist such that:

exist such that:

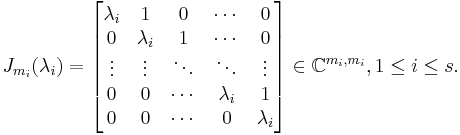

with

where

It is easy to see that

and, since  is block-diagonal,

is block-diagonal,

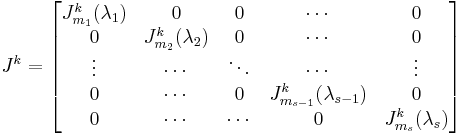

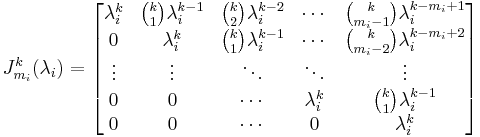

Now, a standard result on the  -power of an

-power of an  Jordan block states that, for

Jordan block states that, for  :

:

Thus, if  then

then  , so that

, so that

which implies

Therefore,

On the other side, if  , there is at least one element in

, there is at least one element in  which doesn't remain bounded as k increases, so proving the second part of the statement.

which doesn't remain bounded as k increases, so proving the second part of the statement.

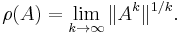

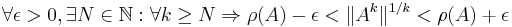

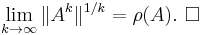

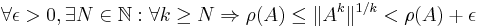

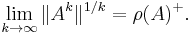

Theorem (Gelfand's formula, 1941)

For any matrix norm ||·||, we have

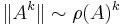

In other words, the Gelfand's formula shows how the spectral radius of A gives the asymptotic growth rate of the norm of Ak:

for

for

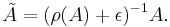

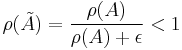

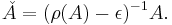

Proof: For any ε > 0, consider the matrix

- Then, obviously,

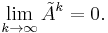

- and, by the previous theorem,

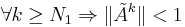

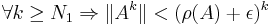

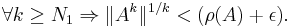

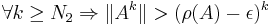

- That means, by the sequence limit definition, a natural number N1 ∈ N exists such that

- which in turn means:

- or

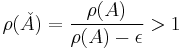

- Let's now consider the matrix

- Then, obviously,

- and so, by the previous theorem,

is not bounded.

is not bounded.

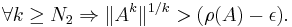

- This means a natural number N2 ∈ N exists such that

- which in turn means:

- or

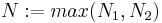

- Taking

- and putting it all together, we obtain:

- which, by definition, is

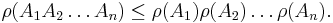

Gelfand's formula leads directly to a bound on the spectral radius of a product of finitely many matrices, namely assuming that they all commute we obtain

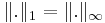

Actually, in case the norm is consistent, the proof shows more than the thesis; in fact, using the previous lemma, we can replace in the limit definition the left lower bound with the spectral radius itself and write more precisely:

- which, by definition, is

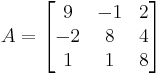

Example: Let's consider the matrix

whose eigenvalues are 5, 10, 10; by definition, its spectral radius is ρ(A)=10. In the following table, the values of  for the four most used norms are listed versus several increasing values of k (note that, due to the particular form of this matrix,

for the four most used norms are listed versus several increasing values of k (note that, due to the particular form of this matrix, ):

):

| k |  |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 15.362291496 | 10.681145748 |

| 2 | 12.649110641 | 12.328294348 | 10.595665162 |

| 3 | 11.934831919 | 11.532450664 | 10.500980846 |

| 4 | 11.501633169 | 11.151002986 | 10.418165779 |

| 5 | 11.216043151 | 10.921242235 | 10.351918183 |

|

|

|

|

| 10 | 10.604944422 | 10.455910430 | 10.183690042 |

| 11 | 10.548677680 | 10.413702213 | 10.166990229 |

| 12 | 10.501921835 | 10.378620930 | 10.153031596 |

|

|

|

|

| 20 | 10.298254399 | 10.225504447 | 10.091577411 |

| 30 | 10.197860892 | 10.149776921 | 10.060958900 |

| 40 | 10.148031640 | 10.112123681 | 10.045684426 |

| 50 | 10.118251035 | 10.089598820 | 10.036530875 |

|

|

|

|

| 100 | 10.058951752 | 10.044699508 | 10.018248786 |

| 200 | 10.029432562 | 10.022324834 | 10.009120234 |

| 300 | 10.019612095 | 10.014877690 | 10.006079232 |

| 400 | 10.014705469 | 10.011156194 | 10.004559078 |

|

|

|

|

| 1000 | 10.005879594 | 10.004460985 | 10.001823382 |

| 2000 | 10.002939365 | 10.002230244 | 10.000911649 |

| 3000 | 10.001959481 | 10.001486774 | 10.000607757 |

|

|

|

|

| 10000 | 10.000587804 | 10.000446009 | 10.000182323 |

| 20000 | 10.000293898 | 10.000223002 | 10.000091161 |

| 30000 | 10.000195931 | 10.000148667 | 10.000060774 |

|

|

|

|

| 100000 | 10.000058779 | 10.000044600 | 10.000018232 |

Bounded linear operators

For a bounded linear operator A and the operator norm ||·||, again we have

A bounded operator (on a complex Hilbert space) called a spectraloid operator if its spectral radius coincides with its numerical radius. An example of such an operator is a normal operator.

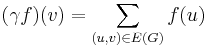

Graphs

The spectral radius of a finite graph is defined to be the spectral radius of its adjacency matrix.

This definition extends to the case of infinite graphs with bounded degrees of vertices (i.e. there exists some real number C such that the degree of every vertex of the graph is smaller than C). In this case, for the graph  let

let  denote the space of functions

denote the space of functions  with

with  . Let

. Let  be the adjacency operator of

be the adjacency operator of  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  . The spectral radius of G is defined to be the spectral radius of the bounded linear operator

. The spectral radius of G is defined to be the spectral radius of the bounded linear operator  .

.

See also

- Spectral gap

- The Joint spectral radius is a generalization of the spectral radius to sets of matrices.